|

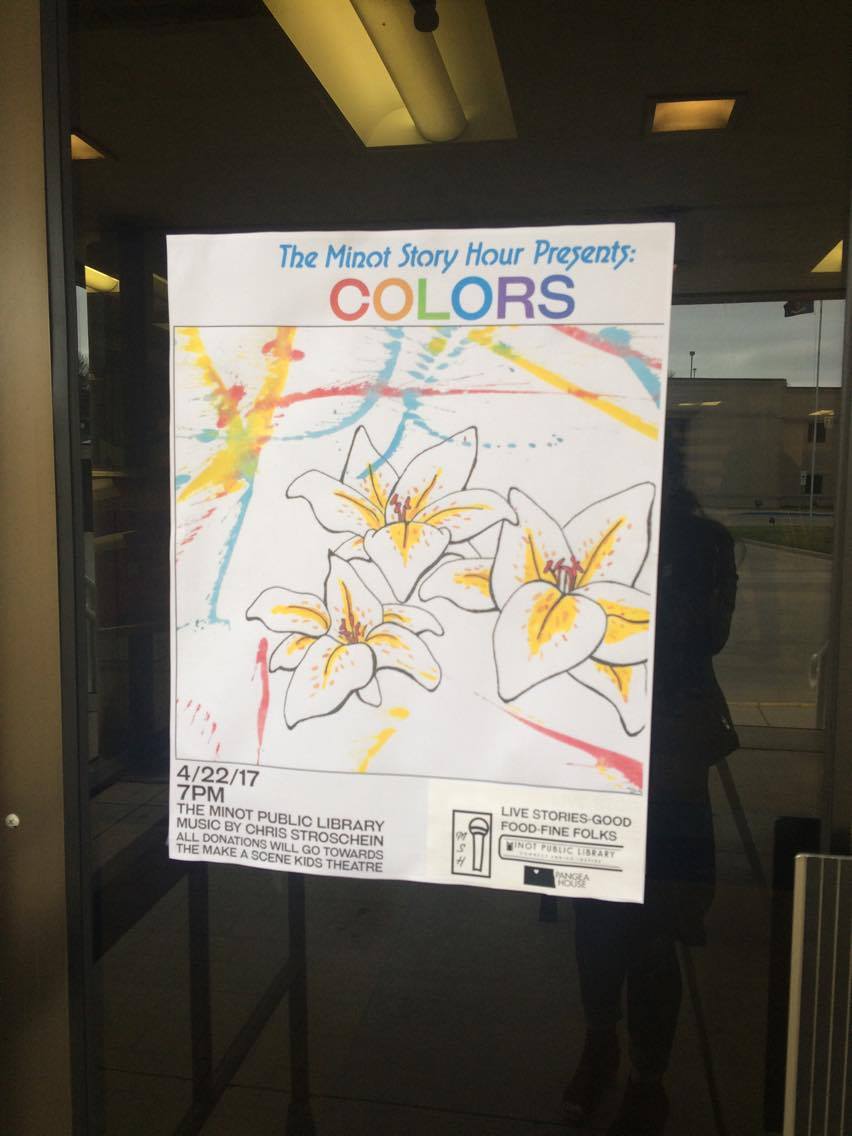

One of the remarkable parts of the human brain is its desire to see things fit perfectly together in a specific space. A nice stack of bowls nestled inside one another just so, or sitting in the passenger seat while a driver expertly navigates a parallel park. It’s like those photos of tiny birds who just hang out on the backs of hippos. Some things, as unseemly as they may be just go together. Which is exactly why my adolescent mind saw the scissors sitting next to the toaster and thought… “I wonder”. Things fitting together were very important to me. This was the golden age of Barbie accessories. Tiny plastic tongs for the lavender grill; a hot pink toothbrush positioned with care on her sparkling sink basin; slipping a purple plastic pump onto her perfectly arched foot in a gesture symbolic of Cinderella only to find a half hour later that it had fallen off and was lost forever, either chewed on by the family dog or little sister. Polly Pockets, Legos, crayons—each had a place. Notches existed on toys for a reason. So too, the toaster’s sole design was for the insertion of objects. Primarily bread, but perhaps other things as well. Even more remarkable than the human brain is the brain of a human mother. As I slowly reached towards the orange plastic handle of the Fiskers, I recall my mother saying “If you stick those in the toaster, you’ll turn green like the Wicked Witch.” I hadn’t voiced my intentions to plunge the blades into the maze of wires, nor was I prone to such impulsive acts, so how my mom predicted what I had in mind, I have no idea. I quickly withdrew my hand and dropped the scissors on the counter. It was a clever threat, not one of punishment, but one of consequences. Like “step on a crack, you break your mother’s back”. I didn’t want to be responsible for that. My mother employed several of these idioms when instructing my sisters and me. If we asked if we could have seconds at mealtimes she’d shrug and say, “eat til you puke.” It was a strangely visceral response for a woman who didn’t allow the use of the word “fart” in her home. I pondered the idea of turning green for a long time. Turning green wasn’t terrible per se. Gumby, trees, Tommy the Power Ranger: many good things were green. But Wicked Witch Green, that was something else entirely. I was more concerned at being held in the same social caste as the Wicked Witch. I mean, the Munchkinks hated her. Munchkins are simply meant to be jolly and they didn’t even feel sorry for her after her sister died—she was tactless. Learn how to read a room, Elphaba. At this point, much of my life was lived through the lens of The Wizard of Oz. We’d been introduced to the film from a young age and I immediately identified with Dorothy. Hadn’t I proved myself to be an audacious young thing always on the verge of trouble—exasperating my elderly aunt and amusing the farmhands as we all struggled to maintain our bland, sepia-lives? I was in fact, none of these things. I was shy and would have never dared challenge any adult authority, especially one who rode a bike with the determination Mrs. Gulch did, shouting accusations, pedaling furiously in heels. Also I wasn’t an orphan and while my mom had actually grown up on a pig farm, our family had retained no agricultural connections, livestock, or farmhands. All Dorothy had was a dog and a dream of living somewhere beyond the rainbow. I also had a dog, but mine was full of chewed-up miniature high heels. Still, I was absorbed by her character. We were thematic sisters—daydreamers who could not be contained by our flat surroundings. I begged my mother for braids. Seeing the world in vivid Technicolor and Cinemascope was simple for me. We grew up in the house my grandfather built. Our midcentury modern home perched on the cusp of a hill allowed for the whole city to open up below us, the plains surrounding Minot visible along the edges. Our living room windows opened up to the landscape in widescreen. The house is very much a product of its time. There’s green shag carpet in the basement with a bright orange bar in the corner for entertaining. A piano painted bright aqua clashes with the mounted fish on the faux brick fireplace. In the 60s it was a groovy place for the neighbors to drink and chat. Yellowed napkins still sit on the bar counter, their edges curling like the legs of dead spiders who have been trapped in drinking tumblers for decades. In the 90s my sisters and I moved our Barbies under the pillars of the piano legs. The bar top transformed into a ballroom floor as our lone Ken doll spun his endless dates in their day-glo dresses, flashing permanent smiles and holding as romantic embraces as their stiff arms would allow. More grown-up opportunities began to present themselves. Our neighbors offered my sisters and me the occasional job pet-sitting for them on weekends. I still secretly played with my Barbies, meticulously re-arranging the playsets, keeping everything in its designated space. The first time I accompanied my twin sister to feed the animals we crept into the house like criminals. “I think this is a shoes-off house,” my sister half-whispered, “The carpet looks like shoes-off carpet.” We deposited our sandals by the door, admiring the more modern aspects of the house. No popcorn ceilings or carpeted bathrooms. They had a leather couch. “GO AWAY,” boomed a voice from the kitchen. “That’s just the parrot,” my sister told me, having already encountered him on a previous weekend. “He’s rude.” While she left to feed the fish, I went to discuss manners with the parrot. As I rounded the corner I was met not with the striking plumage I had expected, but instead with a shriveled creature, not much different than a pre-cooked turkey before Thanksgiving dinner, albeit much skinnier. The bird’s skin was the same color as mine in some patches and dark gray in others. He crouched as I approached, only to hop up and yell “GO AWAY” straight into my face. Atop his head were the only remnants of his once-bold coloring. His eyes were surrounded by yellowed feathers and a single pale plume crookedly stuck up at the back of his scalp. Where wings once were, he tucked comically stubby arms into his tissue-paper skin. The Schwan man delivered frozen fish sticks with more appeal. He shuffled back and forth across his wooden dowel perch and nibbled on the bars of his cage. I reached to touch his beak, but he snapped at my fingers. Then, in what would have been an impressive show had he still had feathers, raised his arms to make himself appear larger. Without proper wings the gesture had no gravity. Without proper wings, gravity was probably a big problem for him. “They told us last time that he’s stressed,” my sister explained, “So he pulls his feathers out. The cats are hiding, but I filled their dishes. Let’s feed this guy and then take out the trash. The litter box stinks.” I couldn’t make myself to go back and see the bald bird. He looked a lot like my grandpa did when he didn’t have his shirt on. Kinda translucent, kinda saggy. Always stressed. Was it possible that a tropical animal and a girl from the Midwest both had the same dream—to be like happy little bluebirds flying over a rainbow? I thought about unhappiness. I thought about it a lot. Persistent thoughts began keeping me up past my bedtime. I’d spend it watching my mother as she completed her nighttime routine. She was often the last to bed, preparing her contacts in their fizzing solution or setting her hair in a curler. From her perch on the bathroom counter, surrounded by the glow of the Hollywood bulbs, I’d watched as she’d inspect her face and pluck her eyebrows. We chatted about our days as she methodically removed one tiny strand of hair after another. As I grew older I began absent-mindedly more drawn to the destruction of things than the putting-together of them. I pulled at split ends of my hair, picked at hangnails and scabs, organized bookshelves before yanking all the books off and starting again with a new system. I was notorious for leaving evidence behind of my unravelling habits. “Where you just sitting on this chair?” my mom shouted from the living room. “Yeah. Why?” She made a gesture to the floor surrounding the area. Tiny loose threads from my socks littered the ground. For at least four years all of my jeans slowly disappeared from the hem up as I would tug and discard the denim fibers. If I was interrupted or told to stop picking, I felt the impulse to parrot the parrot, “Go Away!” Ritualized de-construction became a part of my every day habit. Self-soothing is different for everyone. Some girls in Kansas sing and daydream, some girls in North Dakota unravel old dish towels, some parrots tear out their own feathers. A couple weekends ago my mom and twin sister made a trip to Bismarck to help me pack up my things to make the move to a new apartment. “Kayla Ann, you’ve got to make sure you stay organized in your new place, how do you find anything in here?” my mother chided. I pointed out my meticulously arranged bookshelf. My adult life is a curious balance of chaos and order. I like my dishes stacked neatly but my bed is never made. I handed my sister an armful of unicorn figurines, ornaments, and trinkets to wrap with care in some old, threadbare socks. “Have you kept these since we were kids?” “Just a few.” “You girls need to go through the toys in the basement. It’s making your dad crazy,” mom added. The idea of parting ways with the playthings that provided me with such a sense of peace makes me feel ill. The miniature tea sets that only ever held chocolate milk are still complete. Not a lid is missing. Barbie will continue grinning into eternity. Whereas I gave up trying to maintain order in the physical space of my life, I can’t allow letting the objects of my childhood to leave the place where we all played happily. Dorothy was so relieved to return home and see everything was just as she left it. We took a break to grab lunch downtown. A cardigan in a shop window caught my eye. I went inside and pulled it over my shoulders. I didn’t see a mirror and asked my mom and sister what they thought. “I can’t justify a new sweater,” I said, “I’m moving, you saw all the shit I have already.” “All your stuff looks worn anyway,” my sister interjected, “just get it.” I spun around and inspected the fabric. The shop clerk chimed in from across the store, “That material is so sturdy, you can wash it over and over and it’ll never unravel.” “That’s not a challenge, though,” my sister said. “What do you think, Mom?” I asked. “Go for it. A new look for a new apartment. A new start. It’s very grown up. Besides, you’ve always looked good in green.” This personal essay was read aloud at the April 2017 Minot Story Hour.

The night's theme was "colors".

1 Comment

|

Kayla

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed